Wiggum V2; Happy's Rat Mischiefs

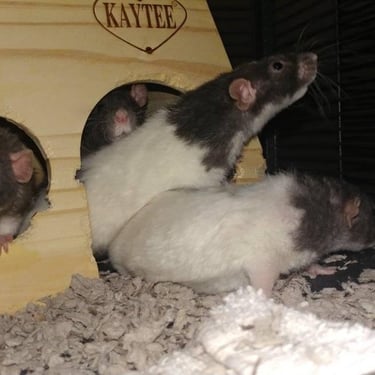

13 very special boys and one special girl.

ARTAUTO BIOGRAPHY

The 4 Ratsmen of the Apocalypse

War was chaos on four legs. He was a small blackish bullet of energy, always instigating, always moving. He and Famine had an ongoing turf war inside the cage, leaving each other visibly scarred. But War also had this mischievous, playful edge. At night, he’d nip at my toes under the covers, like a gremlin reminding me he was there. He once launched himself off a dresser, breaking his leg, but recovered like a champ. I took him and Famine to the World Naked Bike Ride in Chicago—2020 or 2021, I’d have to check the photo. They went with me in a carrier bag, poking their heads out as hundreds of bodies rode by. I think they liked the wind. I think they liked the movement. Some of the photos could be of Famine, war was also black but a slightly smaller body.

Famine, also blackish, was the alpha. The bully. He hoarded food and ruled the cage. But there were cracks in the armor. One night I was lying in bed, and he let me pet him—really pet him. He started to brux, maybe even boggle a bit. For a moment, he softened. He was telling me, in rat language, “I trust you, human.” That memory stays with me. Famine was smart. We had a little game where I’d give him a treat, and he’d run off to stash it. Then one of the others would sniff it out and steal it. He was the only one brave enough to try and leap off the bed when they were free-roaming. He wanted more—always looking for a path.

Death was the small, gray and white runt. He was underweight, slightly deformed, but distinct. He stood out in a way that made me feel protective from the beginning. He only lived about 8 or 9 months. I saw the signs when his time was near. I took him out of the cage and held him to my chest. I told him, like I told my grandmother years before, “It’s okay to go.” And he did. Right there, on me. A hard death. Fitting for his name.

During the eerie, quiet stretch at the beginning of COVID, when the streets were empty and the world felt paused, I brought home four rats from a breeder tank in Rockford, Illinois. I had gone there with my housemate Amy, curious and restless, not expecting to find much. But in a huge tank filled with what must have been over a hundred squirming, destined-to-be-feeder rats, four little lives reached out and clung to mine. I named them Conquest, War, Famine, and Death—the 4 Ratsmen of the Apocalypse. It wasn’t just a clever pun. It was a theme. A prophecy. A story already writing itself.

I hung a printed Wikipedia image of the Four Horsemen in the living room, a tongue-in-cheek shrine to the mythos these four were stepping into. And make no mistake: each of them lived up to their name in a way only a rat could.

Conquest was the gentle sovereign. A fat, jolly, loving black-and-white guy who rarely stirred the pot. He was the one you’d find loafed in a corner, pudgy and pleased, minding his own business. He didn’t get into scuffles. He didn’t need to. He was content. For a while, he had respiratory issues—he went to the vet early in his life, and I remember those moments vividly. At first, I forced medication down his throat with a syringe. But eventually I realized that if I just placed the medicine on a treat and set him in the bathtub alone with it, he’d come around on his own. He got better. Later in life, I suspect he developed a cancerous lump, and I watched him decline. I have photos of him in my arms as his body began to give out. When he finally died, I burned him in my fire pit, and only his head remained—like a relic, a final icon. He left me something. He always had that kind of presence: quiet but permanent.

We held a proper funeral in the backyard. I had a giant Death tarot card tapestry, which I hung on the fence. His brothers were all there—on shoulders, in pockets. A friend spun fire. There was acoustic music. I read from the Satanic Bible. We burned his body wrapped in cloth in the same fire pit all the others would eventually go to. I recorded the moment of his passing. I know some people may be disturbed by that, but I believe Death should be remembered. Witnessed. He was named for it.

Wiggum met the Ratsmen. I took them to Chubby Goat Acres, where Wiggum lives, and let them sniff and squeal and interact. Wiggum had met Izzy Pup too—it felt only right that the family kept meeting itself.

They were my boys. Every time I walked past their cage, I’d say, in the same tone, “My boys!” And they’d come to life, chirping, climbing. I didn’t keep their cage pristine, but I gave them what I could. Leftovers. Turkey bones. Treats. Trash nibblers—like Wiggum, who I always called a trash compactor. They never seemed worse for it. All of them, except Death, lived to be 3–3.5 years old.

When I worked remote, they had the run of the bed behind me. It annoyed my partner at the time—they’d poop on the sheets—but I didn’t care. Eventually I caved and got a plastic cover. Famine was the only one brave enough to try exploring beyond the bed, always hunting for some stair or shelf. When I left the house, I played the radio for them. Just in case they liked it.

They never saw a female. Not once. And strangely, I never saw them hump each other, either. Maybe they were more monk than rat. Or maybe they were just happy.

They lived mostly in shadows. That part of the house didn’t have a window for a long time. The only real sun they got was in their carrier bags on walks with me. Looking back, it feels melancholy. But they didn’t mind. They had light of their own.

And when I tossed them in the air in the “demon drop,” gently catching them again and again, they bruxed with joy. None of them ever puked, flailed, or fought it. They just flew.

The 4 Ratsmen lived like gods in a little cage. They died with fire and music and magic. Their names, their scars, and their love stay with me. This is their chapter. Their first of many tellings.

The Unwell Mischief

After the 4 Ratsmen had settled into their roles and the rhythm of life during the early pandemic, I felt the pull to expand the colony. It wasn’t a simple decision, and in some ways, I still feel complicated about it. The second mischief—who I sometimes refer to as The Unwell Mischief—never quite bonded with me the way the first group did. But they were part of my home, my heart, and my story all the same.

They came from Green Bay, Wisconsin, from a woman who had passed away. I don’t know the full story of her, but I imagine she was someone who loved her animals. Her passing left behind this small group of rats, skittish and not well socialized. I took them in, hoping to give them some kind of peace, or at least a safe landing.

There were four of them in total, all dumbo rex boys with coarse, curly fur—texturally so different from the finer, softer, pointy-eared rats I’d had before. They were less pleasant to pet, physically speaking, but their uniqueness stood out from the beginning. One of them, all gray, was named Pestilence. The others I named Covid (black and white dumbo), Typhus (gray and white dumbo), and Bubonic (another gray dumbo). I’ll need to revisit photos to fully remember who was who, but I remember their essence: ghostly, elusive, and haunted by something I couldn’t quite reach.

These four were fighters—among themselves more than anything else. They were covered in bite scars and nicks, the legacy of dominance struggles and tense social dynamics. It was never malicious neglect; they simply came from a more feral place, and I couldn’t fully bring them in. Still, I fed them, spoke to them, gave them sunlight and stimulation, and cared.

Despite their skittishness, they were part of life at my house. They shared space with the Ratsmen during the overlap. They were present for the changing of generations. When Famine, the last of the original Four, lived long enough to meet the next litter—the Five Brothers—so did the Unwell Mischief. In a strange way, they were the bridge between myth and memory.

They experienced adventure too, in their own quiet way. I remember bringing them—and Famine—to a Chicago Full Moon Jam. I felt self-conscious at the time. Their bodies bore the marks of age and conflict, and I worried people might think I hadn’t cared for them. But I brought them anyway. I wasn’t going to hide them just because they were imperfect. They were nearing the end of their lives, and they still deserved light, music, the flicker of fire dancers.

They spent most of their lives indoors, in shadow. I don’t remember giving them baths like I did later with the Five Brothers. I played with them when I could, though they rarely came when called. They weren’t the kind to leap into my hands. But I still remember their textures, their faces, their silent presence in the room.

I don’t have many clear memories of their individual personalities. That hurts a little to admit, but it’s honest. Time, mental strain, and the subtle distance that can grow between souls made it difficult to track them the way I did with others. But I have photos—lounging like corpses in sleep, nibbling candy apples, balancing across baby wooden blocks with animal letters, falling through flip toys I used as bridges. I’ll dig them up and share them here when I’m ready.

Even with the distance, I cared. Every time I passed their cage, I called out like always: “My boys!” I fed them leftovers, little scraps of my meals. They got turkey bones and soft bites of whatever I was eating. Just like the Ratsmen before them, they were trash nibblers in the best way. The house might have been messy, but there was care in the chaos. There always was.

They died quietly, with little fanfare. No big rituals this time—just memory. Famine died last from that era, but before he went, he and the Unwell Mischief had all met the Five Brothers. A little overlap, a little torch-passing.

They were not forgotten.

The Unwell Mischief

After the 4 Ratsmen had settled into their roles and the rhythm of life during the early pandemic, I felt the pull to expand the colony. It wasn’t a simple decision, and in some ways, I still feel complicated about it. The second mischief—who I sometimes refer to as The Unwell Mischief—never quite bonded with me the way the first group did. But they were part of my home, my heart, and my story all the same.

They came from Green Bay, Wisconsin, from a woman who had passed away. I don’t know the full story of her, but I imagine she was someone who loved her animals. Her passing left behind this small group of rats, skittish and not well socialized. I took them in, hoping to give them some kind of peace, or at least a safe landing.

There were four of them in total, all dumbo rex boys with coarse, curly fur—texturally so different from the finer, softer, pointy-eared rats I’d had before. They were less pleasant to pet, physically speaking, but their uniqueness stood out from the beginning. One of them, all gray, was named Pestilence. The others I named Covid (black and white dumbo), Typhus (gray and white dumbo), and Bubonic (another gray dumbo). I’ll need to revisit photos to fully remember who was who, but I remember their essence: ghostly, elusive, and haunted by something I couldn’t quite reach.

These four were fighters—among themselves more than anything else. They were covered in bite scars and nicks, the legacy of dominance struggles and tense social dynamics. It was never malicious neglect; they simply came from a more feral place, and I couldn’t fully bring them in. Still, I fed them, spoke to them, gave them sunlight and stimulation, and cared.

Despite their skittishness, they were part of life at my house. They shared space with the Ratsmen during the overlap. They were present for the changing of generations. When Famine, the last of the original Four, lived long enough to meet the next litter—the Five Brothers—so did the Unwell Mischief. In a strange way, they were the bridge between myth and memory.

They spent most of their lives indoors, in shadow. I don’t remember giving them baths like I did later with the Five Brothers. I played with them when I could, though they rarely came when called. They weren’t the kind to leap into my hands. But I still remember their textures, their faces, their silent presence in the room.

I don’t have many clear memories of their individual personalities. That hurts a little to admit, but it’s honest. Time, mental strain, and the subtle distance that can grow between souls made it difficult to track them the way I did with others. But I have photos—lounging like corpses in sleep, nibbling candy apples, balancing across baby wooden blocks with animal letters, falling through flip toys I used as bridges. I’ll dig them up and share them here when I’m ready.

Even with the distance, I cared. Every time I passed their cage, I called out like always: “My boys!” I fed them leftovers, little scraps of my meals. They got turkey bones and soft bites of whatever I was eating. Just like the Ratsmen before them, they were trash nibblers in the best way. The house might have been messy, but there was care in the chaos. There always was.

They died quietly, with little fanfare. No big rituals this time—just memory. Famine died last from that era, but before he went, he and the Unwell Mischief had all met the Five Brothers. A little overlap, a little torch-passing.

They were not forgotten.

The Five Brothers

With an overlap of Famine and the Unwell Mischief, a new generation of life arrived in my home. I only meant to get three rats—but I couldn’t tell them apart. Two were dark, two were blond, and one was a strange mix of white and blonde. They came home as a five-pack, nameless and indistinguishable, like a singular entity with five shadows. For a long time—maybe two years—they had no names. Not out of neglect, but because I was still learning who they were. I couldn't separate the brothers so I took them all.

They were the Five Brothers—my last full mischief. Their personalities started to bloom after the eclipse or more I started to really pay attention. Until then, they were an indistinct blur, moving as one and without individual identity. I was a bad dad not noticing their differences. I spent quality time with them in the forest in Southern Illinois telling ghost stories in my van. It was raining out but inside we were bonding.

But everything changed after I did a ritual at Hell Cemetery ion Macleansboro, Illinois during the solar eclipse. I cut myself, danced, laid out artifacts aligned with the sun, and made a vow—to be a better dad. It was strange, spiritual, primal. And when I returned home, I started learning who each of them was. That eclipse was their threshold moment, and my recommitment to fatherhood.

One of them died before he could be named. I still call him Unnamed. I tried everything to save him. He had fallen, I think—something with his spine. He lost control of his back legs, and for a week and a half, I cared for him constantly. I brought him to the vet, dropped around $3,000 on treatments, tried catheter care, hand-feeding, gentle holding. Nothing worked.

When the vet gave up, I was told to take him to the large animal hospital in Urbana—the same one I took Wiggum to when his hoof got caught in the bike spokes. It was the middle of the night, and I was driving, hoping he could hold on just long enough to check in. But he died in my hands before we got there. Ten more minutes and he might’ve made it. I had a panic attack afterward and ended up in the hospital myself.

Unnamed got a real funeral. Maybe one of the best I’ve ever done. There were at least a dozen candles arranged around him, all kinds of strange and meaningful artifacts pulled from deep corners of my house—little tokens of intention. It was just me and the rat boys. They gathered, watched, sniffed at the edges. I don’t think they knew exactly what was happening, but they knew something sacred was going down.

The four remaining brothers carried on.

The Dark Four: Beaselbub, Satan, Lucifer, and Devil

After Unnamed’s funeral, something shifted. I had mourned. I had lit candles. I had cried. But I wasn’t alone. Four dark brothers remained—Beaselbub, Satan, Lucifer, and Devil. And as I shifted into the next phase of being their dad, I turned my attention fully to them. These weren’t just survivors of a mischief—they were their own force, a new era in fur and teeth.

The house became theirs. I let them roam free, setting up ramps on the stairs, tunnels made of cardboard, little jungle gym scenes from whatever I could scrounge together. They learned every inch of the space. Some days I’d find them staring out from the window sills, other times hiding in bizarre spots only a rat could love. But the most sacred place? The basement, next to the water heater. They’d gather there together like it was their temple. I called it their “pow-wow near the flame.” I didn’t interrupt—it felt like a ritual of their own.

There was a brief period when I had to move out of my space and lived in my van. It wasn’t glamorous—I had issues with people moving out, and I needed space. So I packed up what I could, and the rats came with. We lived together in that cramped van for a few days, weathering the awkwardness, the heat, the improvisation. I’d bring them out, let them stretch on the dashboard, offer snacks in plastic takeout containers, and whisper to them that everything would stabilize soon. They trusted me. And I didn’t let them down.

Beaselbub was fat and oafy. He lumbered, waddled, flopped. He wasn’t slow out of laziness—he just moved like gravity pulled on him differently than the others. He brought a dopey kind of peace. Watching him was like seeing a soft little blimp float across the room. When he passed, I missed that weight.

Satan was quieter, but no less present. He wasn’t flashy, didn’t have big moments, but he was there for every journey. In some ways, he was the glue. Always around. Always game to follow the others’ lead. A background presence with a quiet steadiness. He was the rat who didn't demand attention, but earned it with constancy.

Lucifer was the rebel turned alpha. At first, he wanted nothing to do with me. He bit. He lashed out. And I let him. As part of the promise I made after the eclipse, I gave him space to be angry. I let him bite as long and hard as he needed. And slowly, he stopped. Then he started gathering things. Hoarding. Stashing. Building order out of chaos. He was showing me he had purpose—he became the leader. The one who watched the others and took responsibility, in his own wild way.

Devil was the slow one. Not dumb—just calm. Gentle. Careful. That caution may have been what saved him in the overheating incident. When Beaselbub, Satan, and Lucifer all passed in that tragic carrier bag accident, Devil remained. He was the lone survivor of the Dark Four. His chapter is too big to hold here. He deserves his own.

The time with the four of them was chaotic but full. They saw the inside of my van, the firelight of the basement, and the full stretch of the house. They were free in a way that few animals ever get to be in a human’s world. And I was proud to be their dad.

The death of Beaselbub, Lucifer, and Satan was a very unfortunate accident. However, Devil made it and after a while paired him with a female named Mary. This is where this story is going to end for now but there will be a whole blog just on this part of their lives.

-59